We have been dancing near record low temperatures in these parts. It’s not quite as cold as the dark side of the moon, but it is cold enough that the water in the garden hoses is frozen in the morning and there’s frost on the ground. (Also, cold enough that ice needs scraping off the windshield in the morning, which has led me to the discovery that, in the absence of a proper ice-scraper, a Safeway card does the job.) Still, in anticipation of our traditionally temperate late-winter weather here by the San Francisco Bay, we’ve been planning some garden-related fun for the Free-Ride offspring. As you might guess, a lot of the plans have a science-y angle to them.

We have been dancing near record low temperatures in these parts. It’s not quite as cold as the dark side of the moon, but it is cold enough that the water in the garden hoses is frozen in the morning and there’s frost on the ground. (Also, cold enough that ice needs scraping off the windshield in the morning, which has led me to the discovery that, in the absence of a proper ice-scraper, a Safeway card does the job.) Still, in anticipation of our traditionally temperate late-winter weather here by the San Francisco Bay, we’ve been planning some garden-related fun for the Free-Ride offspring. As you might guess, a lot of the plans have a science-y angle to them.

1. The “expired seed-packet” assay (already under way). You know how the seed packets they sell at garden stores indicate the growing season for which the seed is intended? Some of us have a tendency to hold onto unplanted seeds past the intended “plant by” date — sometimes a dozen years past those dates. The most optimistic of the garden books say that most seeds last three to five years. So the sensible thing to do would be to toss them. But then you hear stories about seeds recovered from ancient tombs that have still been viable, and you say, “Nuts to the books, we’re going to see what happens!” Last week we labelled 100 peat pots, filled them with potting soil, and planted seeds from 50 of our old seed packets. (We did duplicate peat pots for each packet in case the position of the pot in the flat relative to the edge, the windows through which light was streaming in, etc., made a difference.) So far, we’ve determined that the arugula and one of the radish varieties are still viable (since we’ve seen sprouts in both sets of plantings for each of these). Given the long germination times for some of the seeds, we’ll be watching the pots for at least a few more weeks before we draw our final conclusions.

By the way, kids are pretty fascinated by the variety of shapes and sizes seeds take. (Tiny little lettuce seeds and big bumpy beet seeds are the local favorites.)

2. Planting by the phases of the moon. Once the frames for our raised garden beds have been built and the beds have been double-dug, we may try to test the hypothesis mentioned by John Jeavons in How to Grow More Vegetables that certain seeds do better planted at particular phases of the moon. Since I think Uncle Fishy might have borrowed our copy of the book, I can’t give you all the details, but it’s purportedly to do with fluctuations in light (from the moon, see) and gravitational pull (also from the moon), and how that works with longer vs. shorter germination times. Yes, it sounds kind of flaky. All the more reason to subject it to empirical test! We’ll sow some of our seeds with the “recommended” phases of the moon, and the same seeds anti-phase. And, to isolate the effects of moonlight and moon-gravity, we’ll put some in the garden beds out in the yard, and others in peat pots on the shelf in the shed that’s out of the path of moonbeams that might get through the shed windows. We’ll report our results when we know them. (Maybe in time for the county fair?)

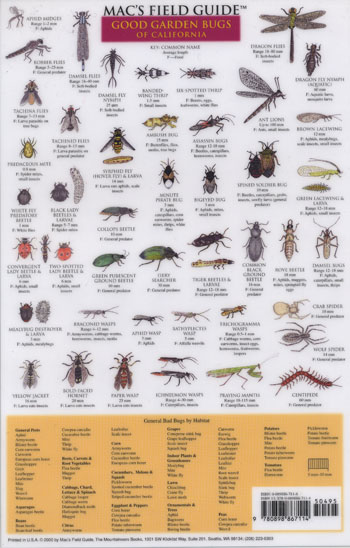

3. Bug census! On one of our garden store treks, the sprogs immediately found this cool laminated field guide to garden bugs of California. On the side shown here, there are pictures of the good insects — the ones you want to have around to make your garden happy. On the other side, there are pictures of the bad bugs that’ll wreck your plants. (The laminated guide also has a little 0 mm to 10 mm measuring scale right on it, so you can get a good estimate of the size of the specimen you’re examining. Also, it has a hole at the top, which means you can hang it from a hook or a nail in the shed when you’re done with it.) The sprogs will be making weekly forays into the garden to report on the types and numbers of bugs they see there. It is likely that they will also be drawing these bugs, or snapping pictures of them with the tiny little digital camerals they got from Uncle Fishy and RMD, in which case drawings or photos will be dutifully uploaded here.

3. Bug census! On one of our garden store treks, the sprogs immediately found this cool laminated field guide to garden bugs of California. On the side shown here, there are pictures of the good insects — the ones you want to have around to make your garden happy. On the other side, there are pictures of the bad bugs that’ll wreck your plants. (The laminated guide also has a little 0 mm to 10 mm measuring scale right on it, so you can get a good estimate of the size of the specimen you’re examining. Also, it has a hole at the top, which means you can hang it from a hook or a nail in the shed when you’re done with it.) The sprogs will be making weekly forays into the garden to report on the types and numbers of bugs they see there. It is likely that they will also be drawing these bugs, or snapping pictures of them with the tiny little digital camerals they got from Uncle Fishy and RMD, in which case drawings or photos will be dutifully uploaded here.

There are no plans to mount a campaign of extermination against the bad bugs — at least not right away — in part because the bad bugs are the preferred source of food for some of the good bugs. We’ll see what population patterns we observe.

4. Gastropod bounties. We are going to try to wipe the slugs and snails off the face of my garden, though. They eat all my best stuff and turn their slimy little noses (or whatever they have in lieu of noses) at the weeds. So, once the vegetable garden is ready to be planted, the Free-Ride offspring will be paid for each slug or snail they pick and turn in. I’m prepared to start with a penny per gastropod (although the elder Free-Ride offspring thinks that’s too low; luckily, the younger Free-Ride offspring thinks it’s fair, which will force the prevailing price down). Once the gastropod populations starting crashing, though (which, I am assured, they will with nightly picking), I’ll happily jack up the bounty to five or ten cents per gastropod. I anticipate we’ll discover not only what it takes to drop the gastropod population below the level at which it munches with impunity, but also what the “fair price” (in the minds of five- to eight-year-olds) is for this kind of labor, and how it relates to how much gastropod-picking work is available.

5. Soil-related activities. Since we’ve discovered some of the perennials we want to plant (blueberry bushes!) like relatively acidic soil, we’ll be checking out the soil pH in various locations in the yard. If we get a second compost pile going (which, given the amount of compostables we generate, seems likely), we may try to see whether composted lemon components (juiced lemon halves, “drops” from the lemon tree, etc.) have a noticeable impact on the pH of the compost produced. We’ll probably also track water retention in the different parts of the yard (since the soil that we started with is heavy clay, but we’ve also got some “trucked in” soil that is relatively sandy, and the vegetable garden will involve digging a fair bit of compost into the native soil).

Now if things would just warm up!

Another experiment might be to verify if it’s true that if you take a pie pan, dig it in so that the lip is at ground level, and fill the pan with beer (the cheap stuff, please) the gastropods will be attracted to the beer, crawl in to the pie pan, and drown.

Given that the moon is currently a cresent as observed from here on Earth, the far side is getting more sunlight than the near side right now. Thus it is probably warmer. It may even be warmer than your California winter- certainly in a week it will be.

Ah, compost!

Your mention of starting a second compost pile reminds me of my grandfather’s composting technique, which it sounds like you probably have room for. This also greatly reduces the amount on turning of compost that needs to be done. It’s a two year process.

First year, pile all your compost in one spot. Turn it after you’ve cleared all the dead plants at the end of the season. In the spring, start a new compost pile for that year, and plant your squashes and cucumbers around the old pile, allowing them to grow over its top. They will thrive on the nutrients and warmth in the soil around the edges of the pile.

At the end of the second season, turn both piles. In the spring, the compost from your first pile will be ready to add to your garden beds, and you’ll have the space to start a new pile. Repeat the process of growing squashes and cukes around the previous pile.

Happy gardening!

I’ve planted basil seeds that turned out to be viable five years after the expiration date.

Aunt Molly decided to clean the corner kitchen cabinent and found some herb seeds of undetermined (but significant) age. Rather than trash them, I’ll contribute them to scientific research. Watch the mail.

I always wondered what Safeway cards were good for.

I had a dog who was great at picking slugs and snails. On summer nights, we used to have to stop him in the laundry room to pick all of ’em out of his fur. Fortunately, his previous owners taught him to come in the door then wait to get his muddy paws wiped off, so we just worked with that.