Following up on an earlier post, I wanted to say a little about the Synopsis Championship that took place last week. It’s sort of a judge’s-eye view of the fair — from a very enthusiastic and impressed judge.

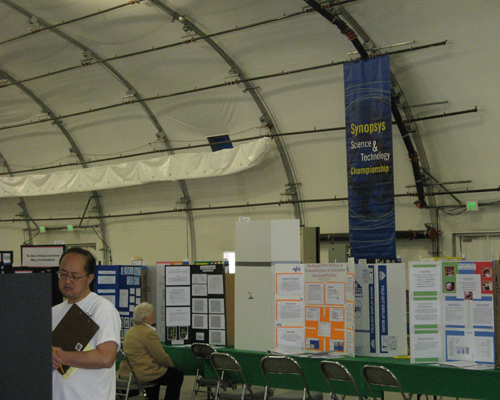

I walked over to the convention center from campus, and it actually took my awhile to find the fair because the last time my teaching schedule was such that I could judge the fair, they held it in the main exhibition hall. This year, it was in its own hangar-like building.

Judges checked in, got their name tags, judging-team assignments, and guidelines for judge and for talking with the students about their projects. We found our team members in the dining area, introduced ourselves, and chatted over lunch.

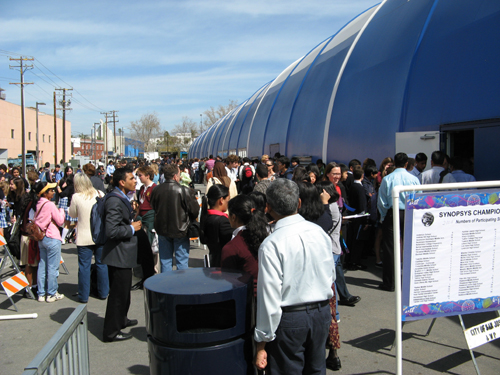

Meanwhile, the students (along with some teachers and parents) gathered outside.

As judges, we were first supposed to evaluate projects (the display poster, project notebook, and abstract) while the students weren’t there. This was a pretty good way to work out just how clearly the written (and visual) materials communicated the details of the project. It also gave us some time to think of good questions and issues to talk about with the students.

I’m not sure what the total number of projects was. My team was assigned to judge ten projects (one of which ended up being a no-show). We had entries by 8th graders in the general areas of chemistry, physics, and microbiology. And, unlike some years when I’ve judged, I think the group of projects assigned to us really worked as a group — the kids were on more or less the same level of scientific sophistication, the questions they were trying to answer were at about the same level of complexity, and all of them were working on their own rather than under the auspices of a working scientist in a lab.

My judging team decided to look at and score the projects separately, both when the kids were waiting to be let in and then when the kids were stationed with their projects. We figured it would make more sense to try individually to apply the judging criteria to the projects we actually had rather than trying to work out a detailed set of a priori principles about how we’d award points.

The organizers actually advised judges to talk to the students individually rather than together. Partly this keeps the kids from having to talk to a group of judges all together (which I’m guessing could be pretty intimidating). Also, it lets the kids “warm up” and improve their spiel, not to mention thinking about answers to questions that more than one judge asks (rather than answering all the questions “cold”). Finally, having the judges talk to the kids serially rather than in parallel helps the kids stay occupied for more of the time they’re required to be right there with their projects.

So, what did we talk with the kids about? I was interested to find out where they got the idea to tackle the problem they did, how they decided on a particular experimental strategy. I wanted to hear about how they decided what data to collect, how they should analyze and interpret that data, and whether they had ideas about what additional data might settle any lingering questions. Of course, I also asked what parts of the project were harder than they foresaw, or took unexpected turns.

All the kids in our judging group were really sharp. They had thought a lot about their projects, and they were all pretty good at talking us through them. (As it turns out, the posters were not very reliable predictors of which kids would be the most articulate.) Some of them had clearly had “lightbulb” moments about their projects — where, for example, they realized that they had stumbled upon an interesting and unanticipated tangle of causal factors, and were starting to think up clever strategies for teasing them apart.

It was pretty cool to see how happy this made them.

After we did our individual scoring of the projects, the teams of judges went back to the dining area and had discussions about which projects in their groups should get awards (first place, second place, and honorable mention within the group assigned to the judging team). These were pretty interesting conversations, since they brought out the piece of the judging criteria dearest to each judge. One judge might use proper data handling as the key for identifying the very top projects, another might prioritize well-chosen strategies for making unbiased measurements, and another might recognize developed plans for further research as the mark of scientific understanding. We told each other what we had seen. We made arguments, and considered arguments, about how best to sort a bunch of really impressive projects. Finally, we made our decisions and turned them in.

It was a really enjoyable afternoon for me. I hope the students had some fun there, too. As far as I could tell from talking to them, they definitely had some fun (along with the inevitable frustration) doing the research they presented to us.

I’ve judged at a couple of Intel ISEFs, and it’s a blast. Feeling jaded with science? Stuck in a rut you can’t see out of? Be a judge at a science fair. Seriously: it will recharge your sense of wonder.

When I was in middle & high school, the county science fair was a “big deal”. It filled the entire mall, and many large scholarships and prizes were awarded.

I recently was excited to be asked to be a judge at my old science fair. It had dwindled to just one side-wing of the mall. The projects were mostly of the type “which laundry detergent works the best”.

I was shocked, so I asked why it had declined so much. Apparently the No Child Left Behind testing occurs right when the fair is scheduled and so nobody can spare time to work on projects. Also, some schools have gone to block scheduling, so students have science class in either the fall semester OR the spring semester. Since the science fair is in early spring, the students either aren’t enrolled at the time, or have just started the semester and haven’t had a chance to complete a project.

It was nice to see in your post that there are still some great science fairs out there. I hope people come up with ways to work around these new developments so that fairs can continue. Those fairs were a big part of why I became a scientist.

Thanks for posting your science fair experience! I’ve mentored several projects, and the kids are great to work with.

I’m glad you had such a good set. I judged for New York City’s science for while I was living there. The last year I was there, they assigned me to judge mathematics. When the judges gathered afterwards, we had to search for projects that weren’t embarrassing to send on. It’s partially because the kids simply didn’t have the mental tools to start addressing the questions even when they found interesting ones (which several of them did). I don’t mean high powered machinery, I mean just the ability to construct arguments to find the consequences of some set of axioms.

On the other hand, one year when I was judging physics there was a student who had worked out a clever new way to address gravitational lensing. By herself. No academic mentor. It was one of those cases where she told the judges the idea, and you could see the jaws drop.

The whole “science fair” thing is new to me. Can I ask a few questions.

1) What sort of subjects were presented?

2) How long do the kids get to work on them?

3) Are they group or individual projects?

4) Are they helped by their schools?

5) Is there some sort of system to prevent “cheating”?