You’ll remember that I tried to work out precisely what was being claimed in the premises behind framing set out by Chris Mooney. At the end of this exercise, I was left with the hunch that one’s optimal communication strategy — and how much scientific detail it will require — might depend an awful lot on what kind of message you’re trying to get across to your audience, to the point where trying to generalize about framing doesn’t seem very helpful. At least, it’s not helpful to me as I’m still trying to understand the strategy.

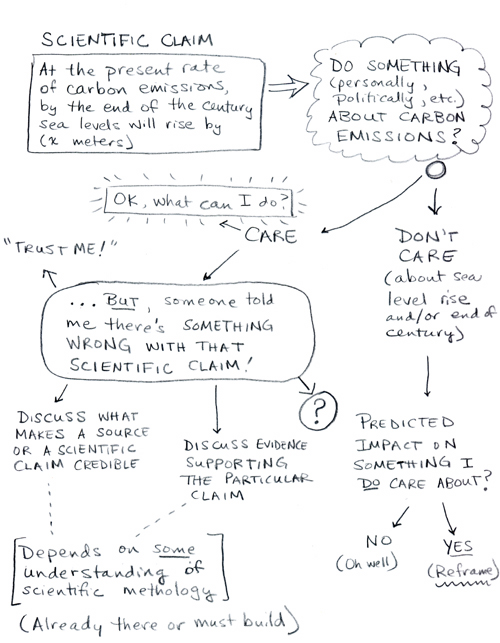

So, I’m hopeful that those who are hip to the framing thing can help me work through a less general example, presented on the hand-drawn flowchart below:

People encounter a scientific claim — in this case, a prediction scientists make from a model they feel pretty good about. People then have to decide what, if anything, to do in light of this piece of information. Scientists are predicting that, if carbon emissions keep up at our current clip, sea levels will show a significant rise by the end of the century? What does that mean to me?

I take it that one issues is whether the audience you’re communicating to cares about the prediction — either about sea levels, or about what things will be like at the end of the century. If neither of those connects with the “core values” of the audience, it seems like the next reasonable question is whether the scientific model makes other predictions about stuff the audience does care about. If it does, you present those predictions (i.e., reframe the information in terms of things the audience cares about). If it doesn’t, you may be at an impasse.

In either case here, it looks like the inner workings on the scientists’ models aren’t part of the conversation — the scientific model is a black box that generates predictions, and the question is whether those predictions are enough to make the audience care and move them to some sort of action. The appeal to core values is in the service of making a scientific prediction personally relevant, not in the service of justifying the scientific prediction.

However, there’s also a possibility that your audience cares about the prediction (because they don’t want Manhattan to go the way of Atlantis), but they’re not moved to action because they’ve heard that the scientific prediction itself is questionable. (Who’s raising a question about the goodness of the science? It might be other scientists, or it might be some of the non-scientific sources of information mentioned in premise 3.) Given an audience of non-scientists, what are the options for countering their other sources who tell them the science here is not good?

You could try to give them some concrete pieces of evidence that support the particular scientific claim. This might require helping your audience grapple with a bit more scientific detail — a few of the important “moving parts” inside of the black box of the scientific model — to see how the evidence you’re pointing to supports the goodness of the model or the plausibility of the prediction. And, it seems to me, this strategy depends on your audience having some understanding of scientific methodology — which means if your audience doesn’t have it already, you have to keep them engaged long enough to help build it. This doesn’t seem to be playing to core values so much as doing actual science education. It’s the kind of thing scientists (at least those who teach) already know how to do. So I’m guessing this isn’t a species of communication that falls under the “framing” strategy Chris has in mind.

Another option might be to try to persuade your audience that the source putting forth the scientific claim and the source raising questions about it might not be equally credible on matters of science. Maybe the audience can be persuaded with some discussion of the burden of proof scientific theories and models must meet for scientists to trust their predictions — but again, this seems to require that your audience understand at least the broad strokes of the scientific method. If they don’t, these broad strokes become scientific details you need to help them understand. Once again, the persuasion doesn’t seem to turn on core values but on some rudimentary understanding of science as a knowledge-building strategy. Is this “framing”?

What other options are there in the case where the scientific claim itself has been called into question? Short of saying, “Trust me!”, I’m not sure what’s left. And I’m especially puzzled about just which “core values” of your audience you could appeal to that would let you counter a challenge to the science without dragging some scientific detail into it.

What would a proper framing strategy look like here? What kinds of core values are the appropriate pivots for persuasion? If someone can fill in plausible details on a specific case like this one, it will go a long way to helping me untangle how framing is supposed to be a distinct strategy from very gentle science education.

I think that you are missing the point of re-framing. It seems to me that what is needed is to change the argument away from being defensive to an offensive one. Being defensive means trying to explain and justify whether AGW is, or will be, occurring. Reframe the argument to attack the denialists as misguided, or unqualified, or financially compromised. For example, when Jim Inhofe gets up and spouts off about AGW not being real, point out – very loudly, strongly and often, that he is in the pocket of the oil industry, that he receives (some amount of) money from them, and that therefore his statements are self-serving and you can’t trust what he says.

That is RE-framing – change the frame, don’t play in their ballpark.

Thanks, Karl — this is a non-(scientific)-detail-heavy way to discuss what makes a source credible (or not), which is a good alternative to discussing scientific credibility itself.

What if the audience comes back with, “Yeah, but I’ve heard those climate scientists have financial interests, too — their grants are tied to predicting doom!” ?

And now they’re playing in our ballpark – we’ve changed the frame. Let’s discuss the comparative value of what a grant is worth versus what Inhofe gets. Then let’s discuss the bases for the money – the scientists get money to STUDY something without prior knowledge of the results, Inhofe gets money for SAYING something without any personal knowledge of the truth of what he’s saying.

In any case, the point is – change the frame, get the argument onto a different subject.

The substance of the message presented in the re-framed discussion suggested by Karl is, unfortunately, a string of ad hominems. I suppose it does manage to appeal to the audience’s core values, to the extent they can be assumed to dislike liars, shills and idiots. On the other hand, there seem to be critics of consensus scientific views to whom such epithets won’t stick — people questioning the science who are quite capable of engaging in critical discussions of scientific methodology. And from their pespective, the re-framing Karl recommends amounts to a refusal to engage substantive criticism. That doesn’t speak well to the intellectual integrity of the re-framers.

Please tell me I’m missing something.

/delurk + apologies for longwindedness

I’m going to jump into the conversation here for various reasons I won’t go into right now, but which mostly have to do with the fact that I’m a(n apprentice) philosopher of science. And, in particular, I want to take issue with the claim that The appeal to core values is [only] in the service of making a scientific prediction personally relevant, not in the service of justifying the scientific prediction. Call this claim value-free justification.

Let’s see. I don’t keep up with the framing discussion, so I’ll assume your model here is accurate. If this isn’t what framing proponents are talking about, fine, I want to talk about value-free justification in the context of schraming instead. I’m not sure what the following has to do with framing anyways.

Now, as an epistemologist of the Analytic-feminist persuasion, I happen to reject value-free justification. To oversimplify a little bit, let’s suppose there’s an agent named JI, and one of JI’s core values is biblical literalism or fundamentalism or something religiousy that’s threatened by some well-established scientific theories. Suppose that JI cares about sea levels rising, and ends up in the `… but someone told me …’ bubble. We (or whoever), following the plan, start to explain to JI about what makes scientific claims, sources, etc., credible. JI responds that this is no good, at least from his perspective (he’s a fundamentalist who believes in the Principle of Charity), because these standards endorse theories that are incompatible with his core values. His core values block justification, at least indirectly.

And if we look back on ourselves, I want to suggest that we should realise how some of our core values have been deployed in justifying scientific predictions. The standards of science (accepted by scientists) are based on our core values, not JI’s, and that’s why we can accept the justification that appeals to them, and JI cannot. Hence not-value-free justification. (For those who are familiar with such names, I’m borrowing heavily from John Dewey and Helen Longino here.)

So (and maybe this is where we get back to framing) we have to engage with JI on the core values level, rather than the level of scientific predictions and public policy. We have to convince him, as it were, to trade in his fundamentalism for something more amenable to science. (NB This applies only to religious folks who have values that are incompatible in exactly the way specified above. Ernan McMullin, Catholic priest and philosopher of science, is my favourite counterexample to inferences from science to atheism.) But, in order to do this, we have to first be honest about the connection between our core values and our methods and standards for knowledge production.

“Reframe the argument to attack the denialists as misguided, or unqualified, or financially compromised.”

If I want to talk about the science and you engage in ad hominem attacks and appeals to authority then I am going to tune you out fast.

So the “believer” is unable or unwilling to discuss the science? Is it because the “believer” doesn’t understand the science? Or because the “believer” is stupider than I am?

Do you want someone to say “Look, you have scientists with PhDs in geosciences being called denialists just because you can’t argue against what they say?”

Hi Janet,

Have you read The Scientist article? It provides answers to many of the questions you pose about framing and provides citations to studies that provide even more answers and details. A PDF of the article along with the recent National Academies summary are available at the link below:

http://scienceblogs.com/framing-science/2008/04/national_academies_on_framing.php

There’s also an interesting cultural predisposition I have been working on with a colleague called “deference to scientific authority.” It gets at how much citizens are willing to simply defer to scientific judgment, unless that judgment is defined for them at odds with some other core predisposition such as ideology or religion. See this study we did in trying to explain American views on plant biotechnology:

http://ijpor.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/edl003v3

Also, the NSF Science Indicators 2008 survey deals a bit with this topic, in terms of comparing the cultural authority of science across a few issues and in comparison to other groups. I had the chance to serve as a consultant on the project and there is lots more to explore in the data that was gathered and available through the GSS. See this link below:

http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind08/c7/c7s3.htm#c7s34

Finally, specifically on climate change, it’s the subject of work I have under review or book chapters in various stages of development, but a short introduction online is this column I recently wrote for Skeptical Inquirer:

http://www.csicop.org/scienceandmedia/beyond-gores-message/

As to some of the more normative issues you raise in your previous post, the goals of framing depend on the context and the issue. It also connects to newly emerging roles and norms for both scientists and journalists. These are things that I discuss in some of my talks. Not surprisingly they were part of the Q&A that went on at Princeton and George Mason last week. It’s also a topic I am addressing in several articles or book chapters and would be happy to send those along when complete.

Best,

Matt

Hi Janet,

I just posted a longer reply with a bunch of links. Not sure if it was sent to your junk folder or not.

Bob and Bill:

I think that you’re missing the point. Ask anyone who has debated a denier – in any field – what happens: the denier makes a statement, the scientist replies in that frame. The denier ignores the rebuttal and makes another statement in another frame, etc. The point is to take the offense away from them. Make your own statements in your own frame – force them to reply.

Now, I am a complete amateur at all of this – both the science and the art of arguing, but it seems to me that this is the point that Nisbett and Mooney are making – not the way that PZ interprets it – to dumb down the science -but to not allow the deniers to control the field.

And, I’m sorry to have to use this analogy, but I think it is appropriate. In sports, (football and basketball in particular) for many years teams played passive defense – waited for the offense to do something and then tried to stop it, over and over. At some point defensive coaches began teaching aggressive defense – attacking, forcing the offense to have to cope with their tactics. They changed the frame. The best example of that right now is the Memphis team in the NCAA semifinals tonight. They rely on attacking on defense, preventing the offense from doing anything they’ve practised.

Dinner time – have to go.

Karl – You seem to be assuming that one confronts what you call “deniers.” Does this epithet apply to those I described earlier as “people questioning the science who are quite capable of engaging in critical discussions of scientific methodology”?

As I said, I’m an amateur. I suggest, at this point, that anyone who still isn’t accepting my interpretation should read Nisbet’s references (above).

A short quote: “Successful framing requires research on how nontraditional audiences perceive science and what aspects of complex science debates are personally meaningful to them. On the basis of those results, further research can explore which phrases, examples, and metaphors succeed best in conveying that meaning.”

Those “phrases, examples, and metaphors” are the FRAME.

It seems to me that the idea of framing is most often presented as strategy to promote effective communication, not as a strategy for dealing effectively with people who deny the validity of scientific standards of evidence. But I was asking about people who do accept the validity of scientific standards, but question whether various wiedely accepted hypotheses actually meet those standards. A frame that amounts to refusing to engage such critics is … askew.

“A short quote: “Successful framing requires research on how nontraditional audiences perceive science and what aspects of complex science debates are personally meaningful to them. On the basis of those results, further research can explore which phrases, examples, and metaphors succeed best in conveying that meaning.”

Those “phrases, examples, and metaphors” are the FRAME.”

The frame repeated often enough becomes fact. That explains why many people give the wrong answers to questions, they don’t know the answer just the frame they picked up somewhere. It also explains why some think I am a denialist and some think I am an alarmist.

The problem with current framing:

You are adding more misconceptions instead of removing them.

You can get some good ideas from the Bad Science site:

http://www.ems.psu.edu/~fraser/BadScience.html

Preamble

This page is maintained by Alistair B. Fraser in an attempt to sensitize teachers and students to examples of the bad science often taught in schools, universities, and offered in popular articles and even textbooks.

Here, I explain what I mean by bad science and provide pointers to specialized pages on bad science within various disciplines. In particular this page points to Bad Meteorology , a page also maintained by Alistair B. Fraser.

When I created this page, in January, 1995, I naïvely expected that other frustrated teachers would rush to build sites devoted to, say, Bad Archeology and Bad Biology. It has not happened. Apparently, most teachers believe everything they teach. Sigh, one is reminded of Lily Tomlin when she said , “No matter how cynical you become, it’s never enough to keep up.”

Noumena writes “Now, as an epistemologist of the Analytic-feminist persuasion, I happen to reject value-free justification.”

Perhaps non-scientific audiences are growing more sophisticated, and appreciate Noumena’s point that we all come from some perspective, which is assumed to color our perception of facts, and how they may or may not support theories. Part of the public media education about science has involved repeated stories about health issues, for example, where scientific consensus has undergone significant changes in public memory (raising questions about the viability of the current consensus).

As well science has been seen to be co-opted by corporate money (cigarettes and pharmaceuticals are two examples), and in any event, is often perceived to he following an agenda set by corporate and government research grants (which may or may not line up with the public’s perception of priorities).

If the public rejects the idea of science as a neutral purveyor of value-less facts supporting unanimously-embraced theories, they can hardly be blamed – science reporting has tended to highlight controversy and disagreement, if only to make science reporting more interesting to the average reader.

In some way framing will make this worse, as it will highlight the ideological nature (always present) of its mission. Rather than organizing facts into theories, and expecting folks to buy into themn, framing suggests that scientists advocate for particular values or issues that are important to the public. This shift will be recognized, and that framing itself will become an issue. Global warming, for example, is splitting largely long liberal / conservative lines, because of how the consequences of global warming have been framed (environment versus impact on the economy).

I’m curious about the “don’t care” entries in the flow chart. Suppose someone says something like, “a catastrophe is likely to occur in, say, 100 years — nuclear war, global warming, whatever — that will result in bad things happening to the humans who are around then. But I won’t be around then, so I don’t care.”

Is there a “formal” (academic, philosophical, technical) discussion of the “ethics” of this which someone can point me to? (“Should” our hypothetical someone care? Why or why not? If they don’t, are they a moral monster? Why or why not?)

A possible way of reframing the global warming discussion is as a risk to future generations, or to reframe again, as a risk to our children. Challenges to the accuracy of scientific claims can be processed as, “what’s the best way to evaluate risks to kids”. Then, instead of true/false, you can proceed with a “what if it happens/what if it doesn’t” analysis. For example, what if you buy little Susan a bicycle helmet, but she never falls off her bicycle? I don’t think many people would think of the money as wasted.

Frames give you a particular set of values, and a particular burden of proof. To “win” the global warming debate, you need a frame in which the future is valued over the present (or at least not devalued). You probably also need the community to be valued over the individual (or at least not devalued). And you need to shift the burden of proof to the other side. Otherwise, you end with, “I don’t think anything is going to happen to me in the future, because nothing much is happening to me now”.

One small detail: calling it “global warming” makes it vulnerable to anecdotes about more severe winters, like “Global warming seems to have missed Buffalo this winter, ha, ha”. People need to be able to fold their own experiences, and what they see on TV, into the frame you’re building. People can reject a claim that no one ever falls off a bicycle based on their own experience. A claim that it’s gradually getting warmer is observably false every winter.