An earlier post tried to characterize the kind of harm it might do to an academic research lab if a recent graduate were to take her lab notebooks with her rather than leaving them with the lab group. This post generated a lot of discussion, largely because a number of commenters questioned the assumption that the lab group (and particularly the principal investigator) has a claim to the notebooks that outweighs the claim of the graduate researcher who actually did the research documented in her lab notebooks.

Category Archives: Institutional ethics

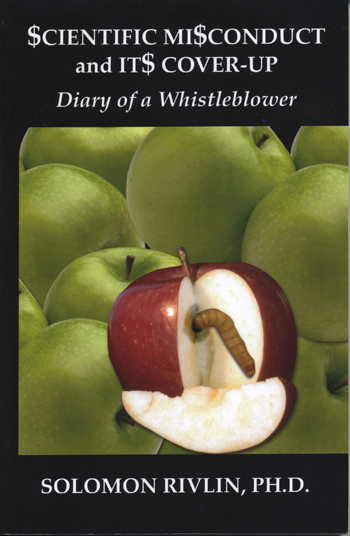

Book review: Scientific Misconduct and Its Cover-Up – Diary of a Whistleblower.

I recently read a book by regular Adventures in Ethics and Science commenter Solomon Rivlin. Scientific Misconduct and Its Cover-Up: Diary of a Whistleblower is an account of a university response to allegations of misconduct gone horribly wrong. I’m hesitant to describe it as the worst possible response — there are surely folks who could concoct a scenario where administrative butt-covering maneuvers bring about the very collapse of civilization, or at least a bunch of explosions — but the horror of the response described here is that it was real:

I recently read a book by regular Adventures in Ethics and Science commenter Solomon Rivlin. Scientific Misconduct and Its Cover-Up: Diary of a Whistleblower is an account of a university response to allegations of misconduct gone horribly wrong. I’m hesitant to describe it as the worst possible response — there are surely folks who could concoct a scenario where administrative butt-covering maneuvers bring about the very collapse of civilization, or at least a bunch of explosions — but the horror of the response described here is that it was real:

The events and personalities described in the following account are real. Names and places were changed to protect the identity of the people who took part in this ugly drama …

I wish I could say that the events described in this book came across as unrealistic. However, paying any attention at all to the world of academic science suggests that misconduct, and cover-ups of misconduct, are happening. Given the opacity of administrative decision making, it’s impossible to know the prevalence of the problem — whether this is just a case of a few extraordinarily well-connected bad actors, or whether the bad actors have come to dominate the ecosystem. In any case, an inside look at how one university responded to concerns about scientific integrity gives us some useful information about features of the academic culture that can constrain and impede efforts to hold scientists accountable for their conduct.

Tenure-track faculty and departmental decision making.

Chad got to this first (cursed time zones), but I want to say a bit about the Inside Higher Ed article on the tumult in the Philosophy Department at the College of William & Mary that concerns, at least in part, how involved junior faculty should be in major departmental decisions:

Should tenure-track faculty members who are not yet tenured vote on new hires?

Paul S. Davies, one of the professors who pressed to exclude the junior professors from voting, stressed that such a shift in the rules would protect them. “If you have junior people voting, they have tenure in the back of their minds, and that would be a motivation to hire someone less impressive than yourself,” he said. In any department with disagreements, Davies added, junior faculty members would also have to worry about offending (or would seek to please) the people who would soon vote on their tenure.

Davies also linked his views to a concern about “standards.” Davies and George W. Harris, the other philosopher who raised the issue of junior faculty members voting, have charged that the department as a whole is reluctant to push nice people to work harder. The two have also raised questions about whether politics and gender enter in some hiring choices, although they have not restricted those concerns to junior faculty members.

“There has to be a check on conflicts of interest between those doing the hiring and the future of the institution in terms of maintaining or even raising standards when standards are at stake,” said Harris. “Here there is no oversight, nor is there in many other places.”

I am tenure-track but still untenured (although I hope to be tenured by this time next year), and I would like to offer some reasons for letting junior faculty vote on new tenure-track hires in their department.

The death of an administrator.

Zuska reminded me that today is the one-year anniversary of the suicide of Denice Denton, an accomplished electrical engineer, tireless advocate for the inclusion and advancement of women in science and, at the time of her death, the chancellor of UC-Santa Cruz.

I never met Denton, and a year ago my feelings about her were complicated. On one side was her clear public voice against unexamined acceptance of longstanding assumptions about gender difference; from an article dated 26 June, 2006 in Inside Higher Ed:

She was in the audience when Lawrence H. Summers made the controversial comments about women and science last year and she was among the first to speak out against them, telling The Boston Globe of Summers: “Here was this economist lecturing pompously to this room full of the country’s most accomplished scholars on women’s issues in science and engineering, and he kept saying things we had refuted in the first half of the day.”

Any gathering of such scholars would indeed have included Denton, who was then dean of engineering (one of her many “first woman” accomplishments) at the University of Washington and was about to become chancellor of the University of California at Santa Cruz. Throughout her career in research (as an electrical engineer) and administration, she was known for being a mentor to women — in the public schools, in graduate school, at faculty levels. Last month, she was named this year’s winner of the Maria Mitchell Women in Science Award — named for the first female astronomer in the United States and given to a person or organization who does the most to advance women in science.

On the other side, shortly before her death, Denton had been the subject of a San Francisco Chronicle story about the amount of money the UC system spent on administrator salaries and perquisites.

Independent confirmation and open inquiry (investigation? examination?): Purdue University and the Rusi Taleyarkhan case.

My recent post on the feasibility (or not) of professionalizing peer review, and of trying to make replication of new results part of the process, prompted quite a discussion in the comments. Lots of people noted that replication is hard (and indeed, this is something I’ve noted before), and few were convinced that full-time reviewers would have the expertise or the objectivity to do a better job at reviewing scientific manuscripts than the reviewers working under the existing system.

To the extent that building a body of reliable scientific knowledge matters, though, we have to take a hard look at the existing system and ask whether it’s doing the job. Do the institutional structures in which scientific work is conducted encourage a reasonable level of skepticism and objectivity? Is reproducibility as important in practice as it is in the scientist’s imagination of the endeavor? And is this a milieu where scientists hold each other accountable for honesty, or where the assumption is that everyone lies?

The allegations around nuclear engineer Rusi Taleyarkhan — and Purdue University’s responses to these allegations — provide vivid illustrations of the sorts of problems a good system should minimize. The larger question is whether they are problems that are minimized by the current institutional structures.

I thought I understood the extent of the bureaucracy here.

I haven’t mentioned it here before, but I’m currently working on a project to launch an online dialogue at my university (using a weblog, of course) to engage different members of the campus community with the question of what they think the college experience here ought to be, and how we can make that happen. The project team has a bunch of great people on it, and we thought we had anticipated all the “stake holders” at the university from whom we ought to seek “buy-in”.

As we were poised to execute the project, we discovered that we had forgotten one:

Probably not the approach to instilling ethics most likely to succeed.

The San Francisco Chronicle reports that the University of California is getting serious about ethics — by requiring all of its 230,000 to take an online ethics course.

Yeah, throwing coursework at the problem will solve it.*

Why do scientists lie? (More reminiscing about Luk Van Parijs.)

Yesterday, I recalled MIT’s dismissal of one of its biology professors for fabrication and falsification, both “high crimes” in the world of science. Getting caught doing these is Very Bad for a scientist — which makes the story of Luk Van Parijs all the more puzzling.

As the story unfolded a year ago, the details of the investigation suggested that at least some of Van Parijs lies may have been about details that didn’t matter so much — which means he was taking a very big risk for very little return. Here’s what I wrote then:

What ever happened to Luk Van Parijs?

Just over a year ago, MIT fired an associate professor of biology for fabrication and falsification. While scientific misconduct always incurs my ire, one of the things that struck me when the sad story of Luk Van Parijs broke was how well all the other parties in the affair — from the MIT administrators right down to the other members of the Van Parijs lab — acquitted themselves in a difficult situation.

Here’s what I wrote when the story broke last year:

The consequences of a chilly climate in the academic workplace.

After my post yesterday suggesting that women scientists may still have a harder time being accepted in academic research settings than their male counterparts, Greensmile brought my attention to a story in today’s Boston Globe. It seems that almost a dozen professors at MIT believe they lost a prospective hire due to intimidation of the job candidate by another professor who happens also to be a Nobel laureate. Possibly it matters that the professor alleged to have intimidated the job candidate is male, and that the job candidate and the 11 professors who have written the letter of complaint are female; I’m happy enough to start with a discussion of the alleged behavior itself before paddling to the deep waters of gender politics.

But first, the story:

MIT star accused by 11 colleagues

Prospective hire was intimidated, they say

By Marcella Bombardieri and Gareth Cook, Globe Staff | July 15, 2006

Eleven MIT professors have accused a powerful colleague, a Nobel laureate, of interfering with the university’s efforts to hire a rising female star in neuroscience.

The professors, in a letter to MIT’s president, Susan Hockfield , accuse professor Susumu Tonegawa of intimidating Alla Karpova , “a brilliant young scientist,” saying that he would not mentor, interact, or collaborate with her if she took the job and that members of his research group would not work with her.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, they wrote in their June 30 letter, “allowed a senior faculty member with great power and financial resources to behave in an uncivil, uncollegial, and possibly unethical manner toward a talented young scientist who deserves to be welcomed at MIT.” They also wrote that because of Tonegawa’s opposition, several other senior faculty members cautioned Karpova not to come to MIT.

She has since declined the job offer.