I have at least six things I really want to write blog posts about at the moment, but the day job is a harsh mistress.

So instead of a content-laden post, you get a list so you can play along vicariously.

In the next nine days, I must:

Cult Book Meme.

I’m still grading, but Bikemonkey tagged me on a book meme and I really want to cross something off my to-do list tonight, so here it is.

The rules: books you’ve read in bold and books you started but never quite finished in italics. (In that latter category, I’ll include books from which I’ve read substantial excerpts without prodding myself to double back to read the whole thing.)

And now for the books:

Passion quilt: a meme for teachers.

More than a month ago William the Coroner tagged me. It is not just that I am slow; this meme is challenging!

Not mush, methodology.

Pop quiz.

Captivated by the colors I saw, I took this picture today.

Any guesses as to what it is?

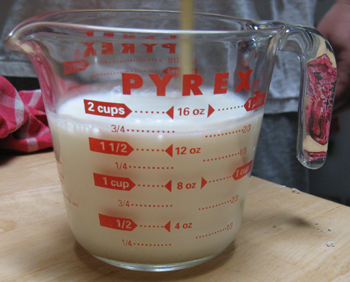

Friday Sprog Blogging: experimental results (milk + lemon juice).

This Friday we’re reporting on one of the experiments we were looking forward to last Friday, the one in which milk is curdled. (We’ll report on our experimental attempts to dissolve an avocado next Friday.)

We started with a little over a cup and a half of whole milk, on the cold side (since it was in the fridge until we were ready to start experimenting). Since we don’t have glass stirring rods at home, we decided to use a plastic chopstick to do the stirring.

As a control, before we started adding lemon juice, we put the chopstick in the cup of milk. The presence of the chopstick had no observable effect on the milk. We stirred the milk with the chopstick for awhile. This kicked up some bubbles in the milk, but when we stopped stirring and let the milk sit for a few moments, the bubbles went away.

We concluded that the chopstick itself doesn’t curdle milk.

Then it was time to bring on the lemon juice.

‘Stop snitching’ as part of the engineering student ethos.

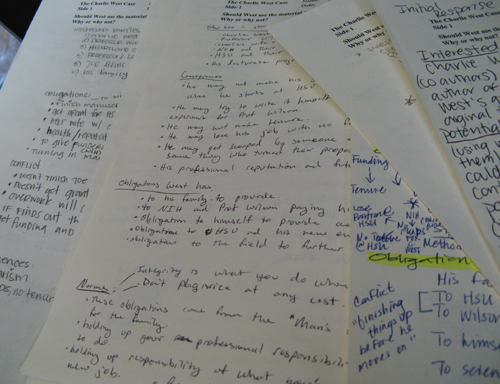

Once again, I’m teaching the relatively new ethics module in “Introduction to Engineering”. Today was the discussion of what kinds of ethics might reasonably govern an engineering student’s behavior, and how these might be important on the road to becoming a competent grown-up engineer.

So of course, we talked about cheating.

Relationships in lab groups.

This post is standing in for a lecture and class discussion that would be happening today if I knew how to be in two places at once. (Welcome Phil. 133 students! Make yourselves at home in the comments, and feel free to use a pseudonym if you’d rather not comment under your real name.)

The topic at hand is the way relationships in research groups influence the kind of science that comes out of those groups, as well as the understanding the members of the group have of what it means to do good science. Our jumping off point is an article by Vivian Weil and Robert Arzbaecher titled “Relationships In Laboratories and Research Communities.” [1]

The love/hate relationship with academia.

Maria has an awesome post about her thoughts upon wrapping up her Master’s thesis. It captures the kind of shifts one can have in figuring out what to do, who to be, and how schooling fits into all of that — and how what’s at stake is as much emotional as it is intellectual. She writes:

I have found that clinging too stubbornly to long-term goals is actually bad for me. Not because the goals themselves are bad, but I tend to become emotionally overinvested in them, and then I freak! out! at the slightest threat to my success. Learning to keep things in perspective has meant, for me, appreciating that lots of things can happen between now and the completion of my Five-Year Plan.

Longtime readers know that my career trajectory underwent some pretty significant changes, so I can really relate to this. I’m going to add just a few loosely connected* thoughts of my own here:

Simon Blackburn on ‘the myth of the scientist’.

Via Crooked Timber, I see that philosopher Simon Blackburn would like to dispel some myths. (He does this in the inaugural article of a Times Higher Education series “in which academics range beyond their area of expertise”.) Of the ten myths Blackburn identifies for busting, the one that caught my attention was “the myth of the scientist”:

Do jokes reveal something about who you’re talking to?

On April Fool’s Day, our local Socrates Café had an interesting discussion around the question of what makes something funny. One observation that came up repeatedly was that most jokes seem aimed at particular audiences — at people who share particular assumptions, experiences, and contexts with the person telling the joke. The expectation is that those “in the know” will recognize what’s funny, and that those who don’t see the humor are failing to find the funny because they’re not in possession of the crucial knowledge or insight held by those in the in-group. Moreover, the person telling the joke seems effectively to assert his or her membership in that in-group. People in the discussion probed the question of whether there was anything that could be counted on to be universally funny; our tentative answer was, “Probably not.”

With this hunch about joking in hand, I wanted to take a closer look at a particular joke and what it might convey.