Coming on the heels of my basic concepts post about the norms of science identified by sociologist Robert K. Merton [1], and a follow-up post on values from the larger society that compete with these norms, this post will examine norms that run counter to the ones Merton identified that seem to arise from within the scientific community. Specifically, I will discuss the findings of Melissa S. Anderson [2] from her research examining how committed university faculty and Ph.D. students are to Merton’s norms and to the anti-norms — and how this commitment compares to reported behavior.

How committed are paleontologists to objectivity (in questions of ethical conduct)?

There’s another development in Aetogate, which you’ll recall saw paleontologists William Parker, Jerzy Dzik, and Jeff Martz alleging that Spencer Lucas and his colleagues at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (NMMNHS) were making use of their work or fossil resources without giving them proper credit. Since I last posted on the situation, NMMNHS decided to convene an ethics panel to consider the allegations. This ought to be good news, right?

It probably depends on what one means by “consider”.

Basic concepts: scientific anti-norms.

A while back, I offered a basic concepts post that discussed the four norms identified by sociologist Robert K. Merton [1] as the central values defining the tribe of science. You may recall from that earlier post that the Mertonian norms of science are:

- Universalism

- “Communism”

- Disinterestedness

- Organized Skepticism

It will come as no surprise, though, that what people — even scientists — actually do often falls short of what we agree we ought to do. Merton himself noted such instances, and saw the criticisms scientists made of their peers who didn’t live up to the norms as good evidence that the tribe of science was committed to the norms. Many of the forces Merton saw pulling against the norms of science came from outside the tribe of science. However, it’s just as reasonable to ask if there isn’t a set of countervailing norms — or “anti-norms” — that come from within the tribe of science.

In this post, I consider the forces Merton saw as working in the opposite direction from the norms. In a follow-up post, I will discuss the findings of Melissa S. Anderson [2] probing how committed university faculty and Ph.D. students are to Merton’s norms and to the anti-norms — and how this commitment compares to reported behavior.

The future of philosophical discourse.

Seen in a comment on A Philosophy Job Market Blog:

… instead of writing “QED” at the end of proofs, I think we should all start writing “pwned.” I want this change to be my legacy to philosophy.

Friday Sprog Blogging: psychic visions.

In pondering the effects of nature versus nurture, the Free-Ride parents have become painfully aware that a large part of their offspring’s environment is provided by the kids at school. This is how the sprogs came to be aware of the existence of The Disney Channel, whose offering seem to grate on the parental units as much as they delight the offspring.

At Casa Free-Ride, the price for choosing a television program your parent does not care for is engaging in some critical thinking about its subject matter.

Dr. Free-Ride: OK, so explain That’s So Raven to me. What is the deal with Raven and those “visions”?

Elder offspring: She’s a psychic.

Younger offspring: Yeah.

Dr. Free-Ride: A psychic, eh? What exactly does that mean?

Senior scientists, give us some good news!

Yesterday I published a post with suggestions for ways junior scientists could offer some push-back to ethical shenanigans by senior scientists in their field. While admittedly all of these were “baby-steps” kind of measures, the reactions in the comments are conveying a much grimmer picture of scientific communities than one usually gets talking to senior scientists in person. For example:

[N]one of your suggestions above would work. Those are all things that we tried. But when the people in a position to do something about it are being rewarded either by their silence or by their complicity, all of the things you suggest have effects ranging from nothing to career suicide.

My experience, sad as it sounds, is that as a junior person in a corrupt research area has two choices: accept the fact that they’re going to get screwed, or find a different field.

So now, I’d like to have a word with the senior scientists.

Where the hell are you?!

Ask an ethicist: How can I stand up to misbehavior in my field?

In the aftermath of my two posts on allegations of ethical lapses among a group of paleontologists studying aetosaurs, an email correspondent posed a really excellent question: what’s a junior person to do about the misconduct of senior people in the field when the other senior people seem more inclined to circle the wagons than to do anything about the people who are misbehaving?

That’s the short version. Here’s the longer version from my correspondent:

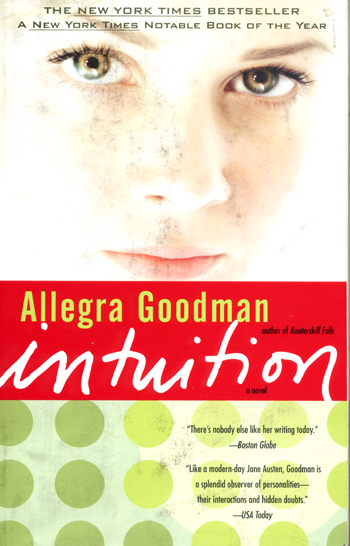

Book review: Intuition.

Allegra Goodman’s novel Intuition was published in 2006, and although I heard very good things about it, I was busy enough with other stuff that I didn’t chase down a copy to read it. Finally, last November, my department chair lent me her copy, insistent that I had to read it when I got a chance — not for any academic purpose, but to do something nice for myself. Between semesters, I finally got a chance to read it.

I have a really good department chair.

Ask a ScienceBlogger, sort of: my life in half a dozen words.

Once again, Dave Ng at The World’s Fair issues a challenge:

If you had to write your memoirs in 6 words, what would they be?

Writing that memoir today, here are mine:

Chemist. Philosopher. Parent. Blogger.

Grown-up? Someday.

Six words fit very nicely in the comments field — what’s your life story?

Friday Sprog Blogging: mutants.

Dr. Free-Ride: Do you guys have a view on which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Elder offspring: Do you mean the chicken or the chicken egg? Or just the egg the first chicken came out of?

Younger offspring: The first chicken came out of an egg, but it was an egg laid by some other kind of creature.

Dr. Free-Ride: And so, knowing as much as you do, you find no paradox here.

Elder offspring: But the Liar’s Paradox is still a real paradox.