One year ago, ScienceBlogs experienced a major expansion. In that year, I’ve been lucky enough to meet some of my fellow ScienceBloggers, though given the size of this operation, I’ve only met the proprietors of about a fifth of the blogs here.

So far.

Happy blogiversary! Cupcakes for everyone, and pictures (with links to the blogs of the pictured bloggers) below the fold.

A project for the genetic engineers.

One of the Free-Ride offspring (which one? who can tell; it was last week) brought home a plant grown from seed as part of a school project.

“We planted the seeds in yogurt containers,” said whichever child it was, “except they didn’t have yogurt in them anymore, just dirt.”

“Well, that’s good,” one of the Free-Ride parental units said (which one? who can tell; see above). “The seeds wouldn’t have germinated in yogurt.”

Of course, that got us thinking …

Friday Sprog Blogging: a chat about mental illness

Assuming the post title hasn’t already scared you away, I wanted to share a conversation I had with the elder Free-Ride offspring about a potentially scary-to-talk-about subject. As you’ll see, it went fine.

And, as a bonus, there’s a cake recipe at the end of the post.

Seeking advice on a rental that might be a risky call.

Because I know some of you are better acquainted with late 20th century science fiction movies than I am, I’m asking for your input on this.

Today, I find myself possessed of a serious hankering to track down and watch Flash Gordon — not the Buster Crabbe version from 1936 (which I watched on public television when I was a kid), but the 1980 motion picture.

Department of Homeland Security and academic labs.

In the June 4, 2007 issue of Chemical & Engineering News (which is behind a paywall accessible only to ACS members and those with institutional subscriptions, I’m afraid) there’s an article on how college and university labs may be impacted by the interim final regulation on chemical security issued recently by the Department of Homeland Security.

In a nutshell, that impact looks like it could involve thousands of hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars for a single university to comply with the rules, even if the chemicals they use fall into those specified by DHS as being at the lowest level of risk. As you can imagine, the colleges and universities are kind of freaked out.

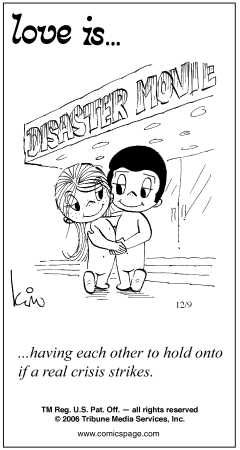

Why you shouldn’t marry your preschool sweetheart.

My better half dropped a comic strip conspiracy theory on me last night. Usually I don’t lend any credence to such theories, but this one has the ring of truth to it.

You know the one-panel strip “Love Is …” that’s been syndicated since 1970?

The one that Homer Simpson described as being “about two naked eight-year-olds who are married”?

Do you ever wonder what might have become of those married former eight-year-olds?

(For that matter, did you ever notice how much alike those naked eight-year-olds looked?)

Brace yourself.

My better half’s theory is that the “Love Is …” kids grew up to be …

Whistleblowing: the community’s response.

In my last post, I examined the efforts of Elizabeth Goodwin’s genetics graduate students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to deal responsibly with their worries that their advisor was falsifying data. I also reported that, even though they did everything you’d want responsible whistleblowers to do, it exacted a serious price from them. As the Science article on the case [1] noted,

Although the university handled the case by the book, the graduate students caught in the middle have found that for all the talk about honesty’s place in science, little good has come to them. Three of the students, who had invested a combined 16 years in obtaining their Ph.D.s, have quit school. Two others are starting over, one moving to a lab at the University of Colorado, extending the amount of time it will take them to get their doctorates by years. The five graduate students who spoke with Science also described discouraging encounters with other faculty members, whom they say sided with Goodwin before all the facts became available.

In this post, I examine the community-level features that may have stacked the deck against the UW whistleblowers. Then, I suggest some ways to change the academic culture — especially they department culture — so that budding scientists don’t have to make a choice between standing up for scientific integrity and getting to have a career in science.

The price of calling out misconduct.

One of the big ideas behind this blog is that honest conduct and communication are essential to the project of building scientific knowledge. An upshot of this is that people seriously engaged in the project of building scientific knowledge ought to view those who engage in falsification, fabrication, plagiarism, and other departures from honest conduct and communication as enemies of the endeavor. In other words, to the extent that scientists are really committed to doing good science, they also have a duty to call out the bad behavior of other scientists.

Sometimes you can exert the necessary pressure (whether a firm talking-to, expression of concern, shunning, or what have you) locally in your individual interactions with other scientists whose behavior may be worrisome but hasn’t crossed the line to full-blown misconduct. In cases where personal interventions are not sufficient to dissuade (or to make things whole in the aftermath of) bad behavior, it may be necessary to bring in people or institutions with more power to address the problem.

You may have to blow the whistle.

Here, I want to examine the case of a group of graduate students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who became whistleblowers. Their story, as told in an article in Science [1], illustrates not only the agony of trying to act responsibly on your duties as a scientist, but also the price you might have to pay for acting on those duties rather than looking out for your self-interest.

Please don’t tell my chemistry profs.

I fell prey to another silly internet quiz, which deigned to tell me which science I am.

It wasn’t chemistry, but …

What do we know about nanomaterials?

Via a press release from Consumers Union, the July 2007 issue of Consumer Reports will include a call for more testing and regulation of nanotechnology:

[T]he risks of nanotechnology have been largely unexplored, and government and industry monitoring has been minimal. Moreover, consumers have been left in the dark, since manufacturers are not required to disclose the presence of nanomaterials in their labeling.