Abel at Terra Sigillata has a post about coscience clauses for pharmacists that’s worth a read. In it, he takes issue with the stand of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), a professional pharmacy organization, recognizing “a pharmacist’s right to decline to participate in therapies that he or she finds morally, religiously, or ethically troubling” while supporting “the establishment of systems that protect the patient’s right to obtain legally prescribed and medically indicated treatments while reasonably accommodating in a nonpunitive manner the pharmacist’s right of conscience.”

I’m going to have a go at the connection between a pharmacist’s personal integrity and his or her professional integrity — in my next post. First, I’m dipping into the vault to offer the way I was thinking about this issue on the ancestor of this blog back in April 2005. Here’s what I wrote then:

Generational differences in gift selection.

It’s my birthday today.

My numerically obsessive parents opted to mark the occasion by sending me Jack Benny and a Hitchcock film.

My offspring had a different idea about what sort of gift was appropriate:

Your vote (for my haiku) can make a difference — but time is running out!

My humble haiku,

Clobbered in the poll — Unless

You vote, intervene.

Voting closes February 26, 11:59 PM EST — so act now!

(If you want to be sure you’re voting for mine, I reproduce them below the fold.)

New blog carnival on women in science, technology, engineering, and math.

Skookumchick has declared a new blog carnival, Scientiae, organized around the broad topic of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (or STEM, for those who like acronyms). She’s soliciting posts that fall under one or more of the following:

- stories about being a woman in STEM

- exploring gender and STEM academia

- living the scientific academic life as well as the rest of life

- discussing how race, sexuality, age, nationality and other social categories intersect with the experience of being a woman in STEM

- sharing feminist perspectives on science and technology

- exploring feminist science and technology studies

Both men and women (and anyone in-between) are welcome to contribute to the carnival as long as the topics are relevant and respectful.

Full details on how to submit one of your posts (or nominate a deserving post on someone else’s blog) can be found here, but submissions are due February 27, so don’t dilly-dally! The first edition of the carnival will be published March 1.

What scientists believe and what they can prove (with a flowchart for Sir Karl Popper).

On the post in which I resorted to flowcharts to try to unpack people’s claims about the process involved in building scientific knowledge, Torbjörn Larsson raised a number of concerns:

The first problem I have was with “belief”. I have seen, and forgotten, that it is used in two senses in english – for trust, and for conviction. Rather like for theory, the weaker term isn’t appropriate here. I would say that theories gives us trust in repeatability of predicted observations, and that kind of trust counts as knowledge. In fact, already the trust repeated observations gives count as knowledge.

The second problem I have is with “the problem of induction”. Science has a set of procedures that observably generates robust knowledge, and the alleged problem is seldom seen. When the terrain and the map doesn’t agree, junk the map.

The third problem I have is with the specific diagrams. Real scientific knowledge production will not yield to any one diagram. So for the philosopher that raises a hypothetical “problem of induction” we could turn around the question and ask why the obvious “problem of description” (which ironically is a real problem of induction 🙂 isn’t bothersome. The scientist answer would probably be as above: “e puor si muove”.

… Without feeling like testability is the end-all of science the diagram is slanted away from testing towards a weaker and in the end nonfunctional descriptive science. Whether we call tested knowledge “a conclusion” or “a tentative conclusion” is irrelevant IMHO, it is a conclusion we will (have to) trust in.

The fourth (oy!) problem I have is with the conflated description the diagram alludes to. In the text there is a distinction between individual scientists and the scientific enterprise. Different entities will obviously use different approaches to knowledge, and if the individual doesn’t need to trust her findings the enterprise relies on such a trust.

These are reasonable concerns, so let me say a few words to address them.

Vote for the best physical science haiku!

Jim Gibbon has opened voting on his academic haiku contest. I urge you to check out all the 17-syllable distillations of scholarly works, but especially those in the physical sciences category.

Two of those haikus are mine. (Technically, one of them ought to be in the humanities category, but I can see how an exploration of philosophical issues in chemistry might look like it belongs in the physical sciences.) Here’s your chance to make me a winner!

Scientific and unscientific conclusions: now with pictures!

This is another attempt to get to the bottom of what’s bugging people about the case of Marcus Ross, Ph.D. in geosciences and Young Earth Creationist. Here, I’ve tried to distill the main hypotheticals from my last post on the issue into flowcharts*, in the hopes that this will make it easier for folks to figure out just what they want to say about the proper way to build scientific knowledge..

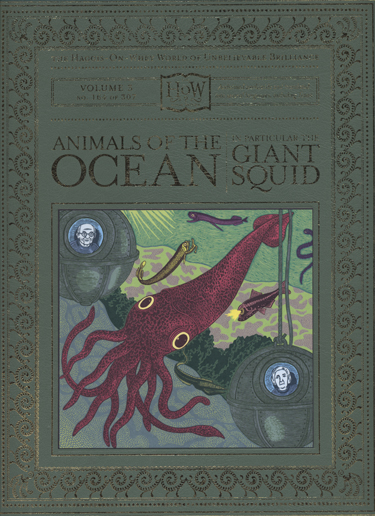

Friday Sprog Blogging: can kids handle science parody?

It will be no surprise to regular readers on this blog that the Free-Ride offspring like books. At this point, it is even possible that their books outnumber their parents’ books, which is almost alarming. (Please send compact shelving and a librarian who can break out some Dewey Decimal on our profusion!)

It will be no surprise to regular readers on this blog that the Free-Ride offspring like books. At this point, it is even possible that their books outnumber their parents’ books, which is almost alarming. (Please send compact shelving and a librarian who can break out some Dewey Decimal on our profusion!)

Naturally, this means the sprogs must grapple with the issue of which books are reliable sources of information and with the related issue of which books are appropriate for children. We consider as a test case Animals of the Ocean: In Particular the Giant Squid.

Knowledge, belief, and what counts as good science: More thoughts on Marcus Ross.

Following up on my query about what it would take for a Young Earth Creationist “to write a doctoral dissertation in geosciences that is both ‘impeccable’ in the scientific case it presents and intellectually honest,” I’m going to say something about the place of belief in the production of scientific knowledge. Indeed, this is an issue I’ve dealt with before (and it’s at least part of the subtext of the demarcation problem), but for some reason the Marcus Ross case is one where drawing the lines seems trickier.

Intellectual honesty in science: the Marcus Ross case.

By now, you may have heard (via Pharyngula, or Sandwalk, or the New York Times) about Marcus Ross, who was recently granted a Ph.D. in geosciences by the University of Rhode Island. To earn that degree, he wrote a dissertation (which his dissertation advisor described as “impeccable”) about the abundance and spread of marine reptiles called mosasaurs which disappeared about 65 million years ago.

Curiously, the newly-minted Dr. Ross is open about his view that the Earth is at most 10,000 years old.