I’m following up on yesterday’s post on where scientists learn how to write (and please, keep those comments coming).

First, Chad Orzel has a nice post about how he learned to write like a scientist. It involves torturing drafts on the rack, and you owe it to yourself to read it.

Second, I’ll be putting up a post tonight about the best scientific writing assignment ever, at least in my graduate school experience. It’s one more professors teaching graduate students might consider adapting.

In the meantime, I want to throw out a set of factors that probably make a difference in the process of helping scientists learn to write. (Use the comments to add factors I’ve forgotten.)

Where do scientists learn to write?

During my office hours today, a student asked me whether, when I was a chemistry student, the people teaching me chemistry also took steps to teach me how to write. (The student’s experience, in an undergraduate major in a scientific field I won’t name here, was that the writing intesive course did nothing significant to teach good writing, and the assignments did very little to improve students’ writing.)

It’s such a good question, I’m going to repackage it as a set of questions to the scientists, scientists-in-training, and educators of scientists:

The impact of blogging on me (a meme).

Dave Munger tagged me with a meme about (among other things) the effect blogging has had on my life. The questions seem worthy of relection, so I’m game:

Basic concepts: theory testing.

I’m a little cautious about adding this to the basic concepts list, given that my main point here is going to be that things are not as simple as you might guess. You’ve been warned.

We’ve already taken a look at what it means for a claim to be falsifiable. Often (but not always), when scientists talk about testability, they have something like falsifiability in mind. But testing a theory against the world turns out to be more complicated than testing a single, isolated hypothesis.

Scientists and non-scientists need to talk.

In a guest-post at Asymptotia, Sabine Hossenfelder suggests some really good reasons for scientists to communicate with non-scientists — and not just to say, “Give us more research funding and we’ll give you an even smaller iPod.” She really gets to the heart of what’s at stake:

Keeping score in academe: blogging as ‘professional activity’ (or not).

During the discussion after my talk at the Science Blogging Conference, the question came up (and was reported here) of whether and when tenure and promotion committees at universities will come to view the blogging activities of their faculty members with anything more positive than suspicion.

SteveG and helmut both offer some interesting thoughts on the issue.

Friday Sprog Blogging: Groundhog’s Day 2007

Last night, while tucking the Free-Ride offspring into bed:

Dr. Free-Ride: Tomorrow is Groundhog’s Day.

Elder offspring: I really hope the groundhog doesn’t see his shadow this year so we can have an early spring.

Younger offspring: Yay! Spring could start tomorrow!

Dr. Free-Ride: Hold on now, “early spring” doesn’t mean spring will start immediately, it means —

Younger offspring: I really want spring to start early because then my birthday will come sooner!

Dr. Free-Ride: OK, you guys realize that what the groundhog sees has no impact whatsoever on how many calendar days are left until May, don’t you?

Elder offspring: Not at bedtime we don’t.

* * * * *

I must have missed the line in my contract that said this is volunteer work.

The faculty where I teach is at a bargaining impasse with the administration of our university system over our contracts. We are hoping that the administration will come back to the table for a real negotiation*, but in the event that that doesn’t happen, there are plans for a system-wide “rolling strike”, with staggered two-day walkouts at each of the 23 universities in the system.

This prompted some opinion pieces in the school newspaper, including this one. There’s a lot I could say about the claims in this piece (the university is going to hire replacement teachers or drop courses from the catalog because of a two-day strike? unlikely!), but there’s a single sentence that I think merits real attention:

If the teachers care more about getting paid rather than the education of the students, I say let them walk.

Marcel Vigneron was robbed!

I simply cannot accept the final judgment in Bravo’s Top Chef (season 2). Marcel should have won.

Sure, I didn’t actually taste the two meals. But simply on the basis of innovation (especially given that the panel of judges seemed to have really good things to say about the flavors of both meals), Marcel should have had the edge. And that’s before we even get into which of the two finalists showed himself to be more ethical and mature (a category Marcel also won on the merits).

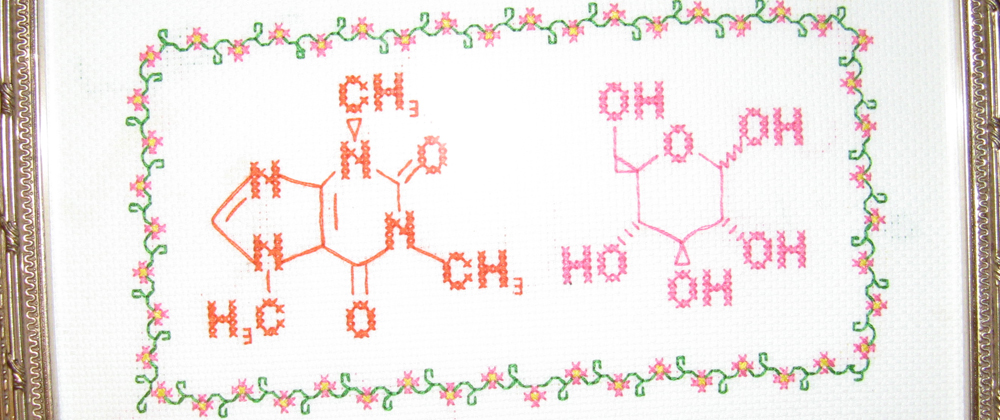

I am now officially interested as heck in learning all about molecular gastronomy. It’s chemistry that non-chemists can see a reason to care about. If Marcel Vigneron or “his people” (if he has “people” at this stage of his career) read this, Marcel has a standing invitation to appear on this blog and educate us about the chemistry of that cool stuff he does in the kitchen.

Basic concepts: falsifiable claims.

Here’s another basic concept for the list: what does it mean for a claim to be falsifiable, and why does falsifiability matter so much to scientists and philosophers of science?