A bunch of people (including Bora) have pointed me to Clay Shirky’s take on #amazonfail. While I’m not in agreement with Shirky’s analysis that Twitter users mobilized an angry mob on the basis of a false theory (and now that mob is having a hard time backing down), there are some interesting ideas in his post that I think merit consideration. So, let’s consider them.

Some thoughts on #Amazonfail.

Those of you on Twitter yesterday probably noticed the explosion of tweets with the hashtag #amazonfail. For those who were otherwise occupied carving up chocolate bunnies or whatnot, the news spread to the blogs, Facebook, and the traditional media outlets. The short version is that on Easter Sunday, a critical mass of people noticed that many, many books that Amazon sells had their Amazon sales rank stripped, and that these books stopped coming up in searches on Amazon that were not searches on the book titles (or, presumably, authors).

What fanned the flames of the frenzy were certain consistencies in what kind of book was getting deranked. Many were books with LGBT subject matter. Some were classic books (like Lady Chatterly’s Lover) or more recent titles with what might be classified as adult themes. Some were books about disability and sexuality. A partial list of the deranked titles can be found here.

The effect of the derankings angered lots of people, indignant that a search on “homosexuality” on the behemoth etailer’s website brought up as top results guidebooks to curing your child’s homosexuality but omitted titles aimed at helping prevent suicide in gay teens. The question to which people wanted an answer was whether these changes reflected concerted policy on Amazon’s part, and whether the problem (as seen by the angry Twitterfolk) was going to be addressed.

As I write this post, the response from Amazon has been anemic to non-existent. The news outlets are reporting that Amazon blames a “glitch” for the derankings. Publisher Weekly reports:

After school experiment: dyeing eggs with plants.

Tomorrow being Easter, a day on which there is some expectation that there will eggs for which to hunt in the backyard (weather permitting), the Free-Ride offspring and I decorated some eggs. We had an old package of oil-based dyes to make “swirled” eggs (the basic idea being that you float drops of the dye on top of cold water, then lowers the egg into the patches of dye, creating a sort of Jackson Pollock swirly effect on the shell).

But for the next dozen eggs, we thought we’d try something a little different. So we gathered some plant materials we thought might have pigments that we could use to create homemade dyes.

Here’s our basic procedure:

Sniffing out bias in a sea of industry research funding.

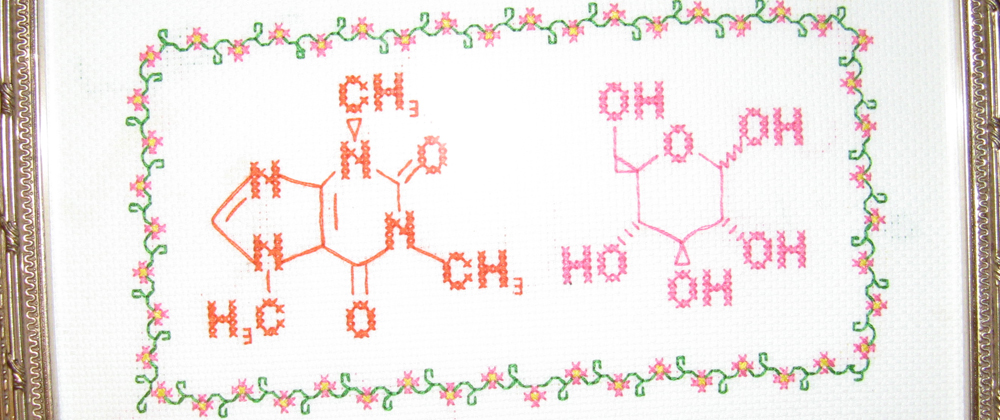

One arena in which members of the public seem to understand their interest in good and unbiased scientific research is drug testing. Yet a significant portion of the research on new drugs and their use in treating patients is funded by drug manufacturers — parties that have an interest in more than just generating objective results to scientific questions. Given how much money goes to fund scientific research in which the public has a profound interest, how can we tell which reports of scientific research findings are biased?

This is the question taken up by Bruce M. Psaty in a Commentary in the Journal of the American Medical Association [1]. Our first inclination in distinguishing biased reports from unbiased ones might be to look at the magnitude of the goodies one is getting from one’s private funders. But Psaty draws on his own experience to suggest that bias is a more complicated phenomenon.

Friday Sprog Blogging: leverage.

This morning, I came upon the younger Free-Ride playing a game.

Younger offspring: I’m playing “launch the bear”.

Dr. Free-Ride: Oh, really?

A chat with Uncle Fishy about beekeeping.

Frequent commenter, sibling, and bon vivant Uncle Fishy recently set up a backyard beehive, but lately he’s been worried about the bees. This came up in a recent online chat:

Dr. Free-Ride: So, what’s worrisome about your bees?

Uncle Fishy: i dont know if they’ll make it

Dr. Free-Ride: 🙁

Uncle Fishy: there were fewer coming out to sting me last night

Uncle Fishy: maybe it was just past their bedtime

Dr. Free-Ride: Maybe they had better things to do than sting you again

The moral thermostat and the problem of cultivating ethical scientists.

Earlier this week, Ed Yong posted an interesting discussion about psychological research that suggests people have a moral thermostat, keeping them from behaving too badly — or too well:

A glimpse into how not to conduct an ethical drug trial.

The Independent reports that drug giant Pfizer has agreed to pay a $75 million settlement nine years after Nigerian parents whose children died in a drug trial brought legal action against the company.

It’s the details of that drug trial that are of interest here:

Friday Sprog Blogging: chatting about math.

Since we’re trying to get out of town for the weekend, Casa Free-Ride is a hive of activity. (As we seem to be passing another cold back and forth, it’s also a hive of mucus. Ew.) But we have time to update you on recurrent topics of conversation this week around the Free-Ride kitchen table.

This week, it’s been all about math.

What are my duties if I offer to help?

At Aardvarchaeology, Martin describes an ethical conundrum:

Let’s say that Jenny’s in bed with a cold and asks her partner Anne to take out a book for her from the library. This Anne does, but on the way home she loses the book. Maybe she absentmindedly puts it on a shelf in the grocery store and it gets stolen, or she forgets to close her backpack and the book falls into an open manhole along the way. Who pays the library for the lost book?

At its heart, this is a question about just what responsibilities one takes on when one volunteers to assist someone.