Do scientists see themselves, like Isaac Newton, building new knowledge by standing on the shoulders of giants? Or are they most interested in securing their own position in the scientific conversation by stepping on the feet, backs, and heads of other scientists in their community? Indeed, are some of them willfully ignorant about the extent to which their knowledge is build on someone else’s foundations?

That’s a question raised in a post from November 25, 2008 on The Scientist NewsBlog. The post examines objections raised by a number of scientists to a recent article in the journal Cell:

Friday Sprog Blogging: dating.

I do not know why, in December, the Free-Ride offspring turn their attention to questions of evidence and testimony. (I do worry, however, that by this time next year the elder Free-Ride offspring may become a 12-25 truther.) This week, the sprogs considered ways to establish dates that don’t rely solely on the testimony of someone who was there.

Younger offspring: I wonder when the first paper airplane was invented.

Dr. Free-Ride: Sometime after the invention of paper, I imagine.

Dr. Free-Ride’s better half: Paper was invented a looong time ago.

Elder offspring: By the ancient Egyptians.

Dr. Free-Ride’s better half: And how far back do you have to go for a civilization to count as ancient?

Younger offspring: More than fifty years ago.

Ethics and population.

Back at the end of November, Martin wrote a post on the ethics of overpopulation, in which he offered these assertions:

- It is unethical for anyone to produce more than two children. (Adoption of orphans, on the other hand, is highly commendable.)

- It is unethical to limit the availability of contraceptives, abortion, surgical sterilisation and adoption.

- It is unethical to use public money to support infertility treatments. Let those unfortunate enough to need such treatment pay their own way or adopt. And let’s put the money into subsidising contraceptives, abortion, surgical sterilisation and adoption instead.

I understand the spirit in which these assertions are offered — the human beings sharing Earth and its resources have an interest in creating and maintaining conditions where our numbers don’t outstrip the available resources.

But, there’s something about Martin’s manifesto that doesn’t sit right with me. Here, I’m not trying to be coy; I’m actually in the process of working out my objections. So, I’m going to do some thinking out loud, in the hopes that you all will pipe up and help me figure this out.

Challenges of placebo-controlled trials.

Back in November, at the Philosophy of Science Association meeting in Pittsburgh, I heard a really interesting talk by Jeremy Howick of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at Oxford University about the challenges of double-blind trials in medical research. I’m not going to reconstruct his talk here (since it’s his research, not mine), but I wanted to give him the credit for bringing some tantalizing details to my attention before I share them with you here.

Faculty unions: organizing when your day-job is a labor of love.

In spring of 2007, after nearly two years without a contract, the faculty of the 23 campuses of the California State University system (of which my university is a part) voted to ratify a contract. Among other things, that contract included raises to help our salaries catch up to the cost of living in California. (Notice the word “help” in that sentence; the promised raises, while making things better, don’t quite get the whole job done.)

The negotiations for this contract were frustratingly unproductive until my faculty union organized a rolling strike that was planned as a set of two-day walkouts at each of the 23 campuses in the system. For most classes, this would have meant losing one instructional day, which would minimize the impact on individual students. As well, a two-day rolling strike would make it pretty pointless for the administration to try to bring in replacement workers. Even with syllabi in hand, our courses are not easily staffed with subs on short notice. (Reasonably, someone would need my notes — some of which are pretty darned cryptic — and if I’m walking a picket line, I’m not going into my office to dig out my notes and hand them over to a scab.)

When strike dates were announced (and, we are told, with some serious political pressure behind the scenes to avert a strike that would have garnered national and international media coverage), the administration came back to the bargaining table with a contract the negotiating team deemed reasonably good (a judgment with which the faculty showed its agreement by voting to ratify the contract).

The staggering thing to me is that we went almost two years without a contract before we could bring ourselves to the point where we were ready to strike.

Now, because California is in the throes of yet another budget crisis, the Chancellor’s office is making noises about revisiting the contract currently in force and renegotiating those promised raises. (Apparently, the state might not be able to afford them, even though we seem to be able to afford raises for administrators.) So the faculty may find themselves in the position of having to fight to get what was promised in the last round of fighting.

There are certain features of a good many faculty members that seem to make it hard for us to embark easily on a job action. Because we’re back in negotiation mode a lot sooner than expected, I think it’s worth examining them.

Year-in-review meme 2008.

Blogging, philanthropy, and commerce. (Oh my!)

I realize that I forgot to mention here that I’ve been writing posts on the Invitrogen-sponsored group blog What’s New in Life Science Research. The blog is hosting discussions about stem cells, cloning, biodefense, and genetically modified organisms. (The cloning discussion just started yesterday.) As you might guess, I’m primarily blogging about the ethical dimensions of these biotechnologies. We’d love to have you get involved with the conversation.

In other news:

Friday Sprog Blogging: hypnotized.

Walking to school the other morning:

Elder offspring: What’s that smell? Is that smoke?

Dr. Free-Ride: Yep. Someone has a fire in the fireplace. Look, there’s the smoke curling out of the chimney. To me it smells good on a cold morning, but when enough people do it, all the little particles in that smoke hurt the air quality.

Younger offspring: I bet it’s nice and warm in front of that fireplace.

Elder offspring: [Dr. Free-Ride’s better half] says that if you stare at a fire — or even a candle flame — long enough, you could be hypnotized.

Sprog commerce.

The Free-Ride offspring have put the wheels in motion to achieve financial independence from their parental units. They intend to make their fortune on T-shirt sales.

Poor deluded kids!

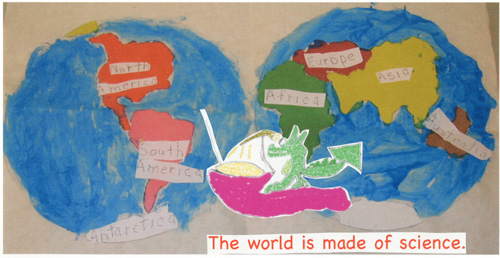

Anyway, they would like you to know that you can score your own copy of this artwork:

on a T-shirt, mug, or totebag, at CafePress.

I would like you to know that we value you as readers whether or not you buy any merchandise.

Holiday chemistry shopping on a budget.

I was marveling at the Chemistry gift guide at MAKE. It has lots of cool items for your budding chemist/mad scientist of any age looking to equip his or her basement/garage/treehouse laboratory. (It’s pretty hard to get fume-hoods installed in a treehouse, but who are we kidding? Most people who dabble in chemistry at home don’t have fume-hoods either.)

The glassware in the pictures is so bright and shiny. (Flashback to the “breakage book” in my high school chemistry class. Also to the hours upon hours of washing glassware in grad school. Still: shiny!) The kids in the pictures from vintage chemistry sets and manuals look so happy and alert. (Also, white and mostly male. And where the hell are their safety goggles?!) The bunsen burners and alcohol lamps look like they could really get something started. (Fire!) The pretty solutions in the pictures (mostly blue, but some yellow and orange) present aqueous-phase chemistry as a wonderland in Technicolor.