A colleague of mine (who has time to read actual printed-on-paper newspapers in the morning) pointed me toward an essay by Andrew Vickers in the New York Times (22 January 2008) wondering why cancer researchers are so unwilling to share their data. Here’s Vickers’ point of entry to the issue:

Category Archives: Tribe of Science

Basic concepts: scientific anti-norms (part 2).

Coming on the heels of my basic concepts post about the norms of science identified by sociologist Robert K. Merton [1], and a follow-up post on values from the larger society that compete with these norms, this post will examine norms that run counter to the ones Merton identified that seem to arise from within the scientific community. Specifically, I will discuss the findings of Melissa S. Anderson [2] from her research examining how committed university faculty and Ph.D. students are to Merton’s norms and to the anti-norms — and how this commitment compares to reported behavior.

How committed are paleontologists to objectivity (in questions of ethical conduct)?

There’s another development in Aetogate, which you’ll recall saw paleontologists William Parker, Jerzy Dzik, and Jeff Martz alleging that Spencer Lucas and his colleagues at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (NMMNHS) were making use of their work or fossil resources without giving them proper credit. Since I last posted on the situation, NMMNHS decided to convene an ethics panel to consider the allegations. This ought to be good news, right?

It probably depends on what one means by “consider”.

Basic concepts: scientific anti-norms.

A while back, I offered a basic concepts post that discussed the four norms identified by sociologist Robert K. Merton [1] as the central values defining the tribe of science. You may recall from that earlier post that the Mertonian norms of science are:

- Universalism

- “Communism”

- Disinterestedness

- Organized Skepticism

It will come as no surprise, though, that what people — even scientists — actually do often falls short of what we agree we ought to do. Merton himself noted such instances, and saw the criticisms scientists made of their peers who didn’t live up to the norms as good evidence that the tribe of science was committed to the norms. Many of the forces Merton saw pulling against the norms of science came from outside the tribe of science. However, it’s just as reasonable to ask if there isn’t a set of countervailing norms — or “anti-norms” — that come from within the tribe of science.

In this post, I consider the forces Merton saw as working in the opposite direction from the norms. In a follow-up post, I will discuss the findings of Melissa S. Anderson [2] probing how committed university faculty and Ph.D. students are to Merton’s norms and to the anti-norms — and how this commitment compares to reported behavior.

Senior scientists, give us some good news!

Yesterday I published a post with suggestions for ways junior scientists could offer some push-back to ethical shenanigans by senior scientists in their field. While admittedly all of these were “baby-steps” kind of measures, the reactions in the comments are conveying a much grimmer picture of scientific communities than one usually gets talking to senior scientists in person. For example:

[N]one of your suggestions above would work. Those are all things that we tried. But when the people in a position to do something about it are being rewarded either by their silence or by their complicity, all of the things you suggest have effects ranging from nothing to career suicide.

My experience, sad as it sounds, is that as a junior person in a corrupt research area has two choices: accept the fact that they’re going to get screwed, or find a different field.

So now, I’d like to have a word with the senior scientists.

Where the hell are you?!

Ask an ethicist: How can I stand up to misbehavior in my field?

In the aftermath of my two posts on allegations of ethical lapses among a group of paleontologists studying aetosaurs, an email correspondent posed a really excellent question: what’s a junior person to do about the misconduct of senior people in the field when the other senior people seem more inclined to circle the wagons than to do anything about the people who are misbehaving?

That’s the short version. Here’s the longer version from my correspondent:

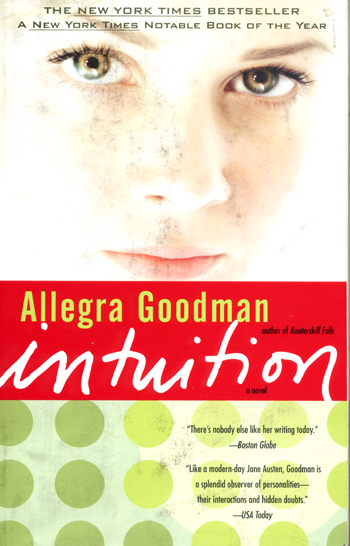

Book review: Intuition.

Allegra Goodman’s novel Intuition was published in 2006, and although I heard very good things about it, I was busy enough with other stuff that I didn’t chase down a copy to read it. Finally, last November, my department chair lent me her copy, insistent that I had to read it when I got a chance — not for any academic purpose, but to do something nice for myself. Between semesters, I finally got a chance to read it.

I have a really good department chair.

The project of being a grown-up scientist (part 2).

In my earlier post, I described the feeling I had as I started my graduate training in chemistry that there was a huge pile of knowledge I would need to acquire to make the transition from science student to grown-up scientist. I should make it clear (in response to JSinger’s comment that I seemed to be reserving the “grown-up” designation for principal investigators) that the student versus grown-up chasm was one that I thought of primarily in terms of how much I felt I’d have to learn by the time the Ph.D. hit my hand in order not to feel like a total impostor representing myself as a chemist. This was the biggest, scariest to-do list I had ever imagined, but I also couldn’t imagine that it was possible to be a successful academic chemist without being to put check marks next to most of the items on it. There were some grad students in the cohorts a few years ahead of me who seemed to be making good progress with that to-do list. And, there were some PIs who clearly hadn’t done so well with it … but none of them were “successful” in the way I wanted to be (although some were officially quite successful in terms of funding and publications).

For all the talk of extended sojourns in grad school or postdoctoral positions infantilizing trainees, I wouldn’t want to claim that trainees are intellectually or emotionally immature. But that kind of maturity isn’t what’s at the heart of being a scientific grown-up. Rather, it’s about a certain kind of facility in navigating your professional environment — from the lab or the field, to the hunt for funding, to the communication of your results and insights to other scientists, to the other sorts of interpersonal negotiations that make the science happen. It’s being a full member of a professional community, taking your responsibilities to that community seriously, and being invested in the direction that community goes and how well it functions.

I wanted all that — plus, to get my experiments to work, so I could actually write a dissertation and get my degree in a reasonable number of years. But it didn’t take long at all to discover that most advisors don’t talk with their trainees about the arcane knowledge the grown-ups seem to have. Obviously, this would make getting that knowledge much harder.

Why aren’t there regular discussions between advisor and advisee about how to be a grown-up scientist?

Rules, community standards, and policing: Casey Luskin and ResearchBlogging.

You may have been following the saga of intelligent design proponent Casey Luskin’s use of the ResearchBlogging.org “Blogging on Peer-Reviewed Research” icon in a way that didn’t conform to the official guidelines for its use.

The short description on ResearchBlogging’s mission says:

Research Blogging helps you locate and share academic blog posts about peer-reviewed research. Bloggers use our icon to identify their thoughtful posts about serious research, and those posts are collected here for easy reference.

The guidelines for using the spiffy icon include registering with ResearchBlogging, something Luskin did not do at first in the post for which he used the icon. However, Luskin made changes that, in his estimation, brought his post into compliance with the guidelines. Did he succeed? And, is there any effective way for a community to enforce compliance to the spirit of its rules, rather than simply to the letter?

Two scientists (‘we’re not ethicists’) step up to teach research ethics, and have fun doing it.

In the latest issue of The Scientist, there’s an article (free registration required) by C. Neal Stewart, Jr., and J. Lannett Edwards, two biologists at the University of Tennessee, about how they came to teach a graduate course on research ethics and what they learned from the experience:

Both of us, independently, have been “victims” of research misconduct – plagiarism as well as fabricated data. One day, while venting about these experiences, we agreed to co-teach a very practical graduate course on research ethics: “Research Ethics for the Life Sciences.” The hope was that we could ward off future problems for us, our profession, and, ultimately, society.