In my last post, I allowed as how the questions which occupy philosophers of science might be of limited interest or practical use to the working scientist.* At least one commenter was of the opinion that this is a good reason to dismantle the whole discipline:

[T]he question becomes: what are the philosophers good for? And if they don’t practice science, why should we care what they think?

And, I pretty much said in the post that scientists don’t need to care about what the philosophers of science think.

Then why should anyone else?

Scientists don’t need to care what historians, economists, politicians, psychologists, and so on think. Does this mean no one else should care?

If those fields of study had no implications for people taking part in the endeavors being studied, then no, I don’t think anyone should care about them. Not the people endeavoring, nor anyone else. The process of study wouldn’t lead to practical applications or even a better understanding of what was being studied – it would be completely worthless.

Let me take a quick pass at the “why care?” question.

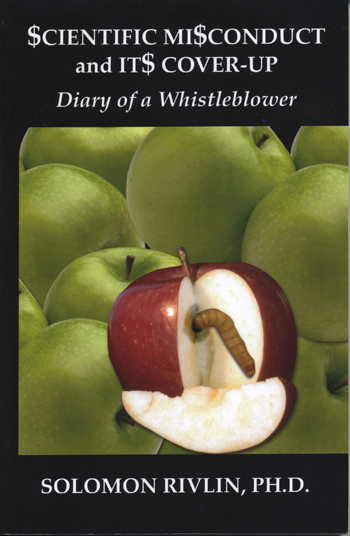

I recently read a book by regular

I recently read a book by regular